Shelby Mustangs are among the Holy Grail of collectable 1960s US sports cars. The fourhere – including a brace – are some of the rarest, most sought after and most valuable of them all

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Consequuntur ab unde quas, laboriosam quaerat amet, cumque blanditiis doloribus laudantium eveniet harum distinctio. Assumenda at obcaecati aliquam dolore reprehenderit, quos veritatis!

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Consequuntur ab unde quas, laboriosam quaerat amet, cumque blanditiis doloribus laudantium eveniet harum distinctio. Assumenda at obcaecati aliquam dolore reprehenderit, quos veritatis!

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet consectetur adipisicing elit. Consequuntur ab unde quas, laboriosam quaerat amet, cumque blanditiis doloribus laudantium eveniet harum distinctio. Assumenda at obcaecati aliquam dolore reprehenderit, quos veritatis!

Though purists feel Shelby lost its southern California mojo from the move, what they tend to overlook is the unquenchable desire to create hotter performing cars never left Carroll, and his key personnel. Experimentation continued apace, and in 1968 Shelby’s muscular GT theme advanced when the GT500KR became available with a more powerful 428 Cobra Jet V8, extra bracing, different exhaust and, on 4-speed KRs, staggered shocks.

In 1969 the GT350 and 500 gained new bodywork that was vastly different from all other Mustangs, but with the Mach 1, Boss 302 and Boss 429 also in Ford dealerships, the end was approaching. In February 1970 with no fanfare whatsoever Shelby and Ford parted ways, and over the next several years Shelby Mustangs were simply used cars, continually depreciating so most anyone with desire and a little spare change could acquire one. Indeed, back in the early 1970s 1965-66 GT350s could be purchased for less than $1,500. Then the first oil crisis hit. Enthusiasts wondered if they would ever see engaging performance cars again, and interest in Shelby Mustangs started to blossom. A mystique that surrounds something special was becoming recognized, and this was especially true in the mid/late 1970s malaise of interesting, new automotive offerings. That awakening raises a question: What causes such mystique to originally form?

In what may seem a blasphemous comparison on first glance, we can identify many of the elements by examining the Modena area, its famed constructors, and comparing them with Shelby and these Mustangs. We’ll start with a broad picture: Both central Italy and southern California have long standing cultures of speed that stretches back into the 1920s. In Modena, testing was done on the street, competitions were held at circuits in town and later, the Aerautodromo di Modena; in southern California, the dry lakes and local circle tracks were the proving grounds. Following World War II both locations saw a large influx of engineers and craftsmen looking for places to apply their skills, and word quickly got out that speed shops and specialist manufacturers were hiring.

Some constructors’ reputations would become lofty enough to spread around the world, and over the years people flocked multiple time zones to work for them. For instance, Bob Wallace left New Zealand and would spend time at Ferrari and Lamborghini; several years later Phil Henny traveled from Switzerland to southern California to work for Carroll. When each left their home country, neither spoke the tongue of the land to which they migrated.

For locals the process was far easier, some arriving at factories in cars that inadvertently became “resumes.” In 1957 Giotto Bizzarrini interviewed at Ferrari, traveling in his modified Fiat Topolino that was his graduating thesis from college. The engineer later told me it was Ferrari’s seeing that car that got him hired. Some seven years after that southern Californian hot rodder Bernie Kretzchmar drove to Shelby to apply for a job. He pointed out not one person reviewed his application; instead, they crawled over and under his ’32 Roadster that appeared on the cover of Rod & Custom. He too got a job.

Luring them were the charismatic characters behind the companies. Whether named Shelby, Lamborghini, Ferrari or some other name ending in a vowel, employees would walk through fire for these larger-than-life figures to be part of the special atmosphere they and their organizations created. Racer John Morton told me about foregoing evening activities to head back to the Shelby factory: “I would return after dinner because those employees that were of any value…had something going on they had to get finished, and I would come back just to watch them.” That sounds much like what former Lamborghini chief engineer Gianpaolo Dallara said about working on the Miura and 350GT: “We were there all the time. It was so exciting and happily we did not realize how difficult it was.”

These “individuals of value” were people like Maserati’s chief engineer Giulio Alfieri, who could “create something from nothing,” according to Dallara. At Shelby the magician was Phil Remington, whose uncanny ability to devise a solution to most any problem meant he usually solved it the first time he tackled it.

Another component to mystique are the test drivers, memorable men with an innate feel of how to make a car better. Guerrino Bertocchi at Maserati, Bob Wallace with Lamborghini, and Giotto Bizzarrini at Ferrari, Iso and elsewhere were masters at developing and refining road models and/or competition cars. In southern California Ken Miles helped transform Shelby’s Cobra, Daytona Coupes, GT40s and GT350s into world-beaters, and in 1966 he would one-up his Italian counterparts by winning Daytona, Sebring and realistically, Le Mans.

This brings us to the machinery these individuals made and specifically, the Mustangs seen here. The creators’ injected their DNA into each, and whether the cars were built by Shelby or the competition, basically all had the same mission: to go faster than the guy (or gal) next to you.

Carroll’s organization may have utilized mass-production parts more than his Italian counterparts, but the results were the same. Race winners emanated from their respective factories, numerous components were designed and/or machined in house, and that formed an ethos to create seriously engaging road cars. The 1965 and ‘66 GT350s are charismatic performers, enthralling driver and passenger alike with nimble handling, superior cornering and braking, and a solid lifter engine that loves to rev while sounding like music. At the time of our photo shoot all the Shelbys were part of auction impresario Craig Jackson’s collection; the GT350 coupe is one of 521 made in 1965, and was a single-family owned, 19,000-mile example that sat untouched for 30+ years. “I never had a streetcar from 1965,” the diehard gearhead reflects, and after its purchase “an idea came up: could we restore (it) to go win all the awards, which we did…(At) the Mustang Club of America it won the Thoroughbred Class and the Authenticity Award, which means it has to have 99% of the parts it came with on the assembly line.”

While Craig jokes the difference between production line and NOS parts is their price, because the ‘65 had so much assembly line “unobtanium” on it, “it’s the only car in my Shelby collection I don’t drive,” he said shortly after the shoot. “I want to take it out and smoke the tires.” Not trusting himself to have such restraint, he decided to part with it and at Barrett-Jackson’s March 2021 sale, it brought a world record $962,500.

The group highlights another element of mystique: rarity. One-offs, handbuilt prototypes, experimentation and eye-catching coachwork were Italian hallmarks in the two-plus decades after the war. Shelby too had its share of such machinery, and also made what in Italy were called fouri serie cars—which is where the GT350 Convertible comes in. Ferrari and coachbuilder Sergio Scaglietti constructed 10 NART Spyders in 1967/68; Shelby built four GT350 Convertibles in ’66.

Powering them was a 306-horsepower 4.7-liter V8, and all were individually spec’d with different colors and options. Craig’s is one of two 4-speed cars, the only one in red, and it’s the Shelby he uses the most. “After I bought it,” he says, “we got all the bugs out. The clutch was chattering away, and the cam had flattened out. It’s restored but not to the degree of the ’65 and it’s a lot of fun to drive.” He often uses it to commute to work and it’s the one I most wanted to try, but threatening rain and the need to complete our shoot before the heavens opened up didn’t allow that. About its value, the ’66 green convertible with an automatic transmission sold last year at auction for $1.1. million; this is very likely somewhere north of that.

While just four made is definitely rare, one-offs may be the most coveted road cars of all. In the 1950s and early ‘60s Ferrari had a number of models that were peppered with one-offs during their production runs, and Maserati did the same with their A62000, 3500 GT and 5000 GTs. In the 1960s Shelby built the GT500 Super Snake, Green Hornet and Little Red, all one-offs with “take no prisoner” attitudes. The latter two are seen here, and Little Red introduces another element of mystique: urban legends.

In August 1966, Shelby ordered three big block Mustangs to start the GT500 development process: a convertible, a fastback that would become the production template, and a notchback. The last became known as Little Red, a name given to it by Shelby’s chief engineer Fred Goodell, who used it regularly.

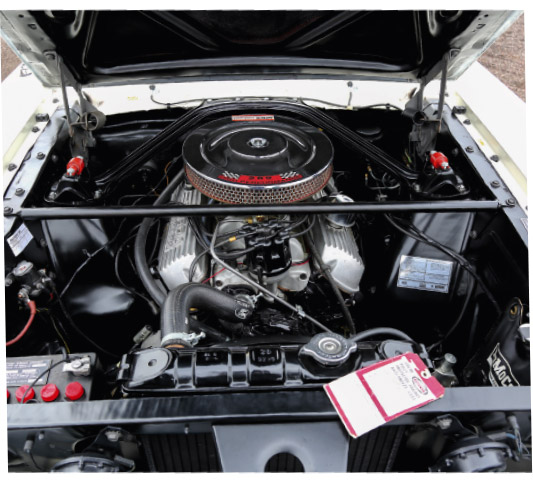

“When it arrived at Shelby American in southern California,” Craig notes, “it became their test bed for engineering innovation.” Changes were numerous, and constant. Jackson’s in-depth research indicates it came with a 428 V8 fitted with two four barrels, at some point it likely had Lucas mechanical fuel injection, and single and double superchargers (the latter registered 600 horsepower on the dyno). The three-speed automatic transmission got an experimental tail shaft, there were special rear brakes, massaged exhaust, and the cosmetics saw numerous changes as different ideas were tried.

To comprehend Little Red’s reputation, Charles Fox’s column in Car & Driver’s April 1978 issue recounts a drizzly southern California evening spent behind the wheel. He noted it “was as quick as the Vicar’s daughter to a hundred, but the real magic came between a hundred and when the nose started to get airborne (at) 135-140 mph. It was annoying having to lift with fifteen hundred revs in hand.” Eye-opening stuff for the era, and even more eye-opening was his ending up in jail for exhibiting such speed…

After three years of tearing up southern California and Michigan’s asphalt, “Little Red was sent to Kar Kraft in Brighton, Michigan sometime in 1970,” the “1965-1967 Shelby Mustang Registry, 4th edition” states, “and unceremoniously crushed.” For decades, that’s what Shelby historians and the Mustang world believed so when noted restorer Jason Billups suggested to Jackson and crew, “What about Little Red?” they rolled their eyes it might still be out there, somewhere. As Shelby American’s marketing manager Scott Black noted, “You cannot find what cannot be found.”